Onlookers hummed over the future of feminism in a white-walled room adorned with works of empowerment from 20 women artists at One Art Space in Tribeca.

With the #MeToo Campaign came power.

A desire to further that power is what lead curator Marina Dojchinov to open the show “She Is,” a collection of sculpture, mixed media, paintings and photography.

“It is important to empower women to stand up and be counted,” Dojchinov said. “We do matter, we are important and we will be heard.”

According to the National Endowment for the Arts, 51% of visual artists are women, and on average, women artists earn $0.81 for every dollar a male artist earns.

“The future is female,” Dojchinov said. “I view female artists as the driving force in the art scene as the inequality gap closes.”

Elsa Marie

More than 500 people packed the gallery, which housed guests an hour and a half past the show’s closing, the event was graciously sponsored by Rockefeller Vodka.The population was split evenly between men and women.

Artists’ stories ranged from overcoming an eating disorder, to leaving an abusive relationship, to breaking past stereotypes professionally, to being forced into feminism based on reactions to the art. The reoccurring thread in all of the artists’ stories was that women have always been powerful, and that they hoped their art would help further demonstrate this strength.

Below are a few of those stories:

Debbie Dickinson

Debbie Dickinson

Debbie Dickinson is a super model who has appeared on the cover of Vogue 18 times. Her career includes working as an actress, journalist, fashion expert, art curator, nature photographer, as well as owning a marketing and public relations company. She is the mother to abstract-futuristic artist Evan Sebastian Lagache.

To move past modeling in the 80s, Dickinson had to convince acting agents that she could do more.

“What they try to do is stereotype you,” she said. “My predisposition in the acting business was basically, they knew me as a model, so casting agents would say, you’re not an actor; you’re a model.

“The modeling industry trains you to accentuate your beauty. It’s hard to wash it down unless you drink a lot before you show up, or you don’t sleep a lot, or you have a magnificent makeup artist who degrades the illusion of what you’re born with. So, when you walk in as a beauty in the industry, you’re pigeonholed.”

She went on to act in movies and Off Broadway productions. Finding balance through more than three decades of sobriety, she continued to expand her career in other realms and was tapped to include her nature photography, a selection narrowed down from more than 15,000 photographs, for the show “She Is.” The work focuses on the beauty in nature in New York, at its beaches and a macrocosm of the city’s insects.

The artist stated that she has surpassed the pigeonholing that could have held her back.

“No longer, because I’m writing my own films, I’m writing my own books, I’m driving my own car.”

Allison Harrell

Allison Harrell

Artist Allison Harrell played soccer as an adolescent alongside her best friend. In doing so, their bodies took on an athletic shape. They’d pretend to be exaggerated characters from the television show American Gladiators. They were the only girls to sign up for the weightlifting gym class.

At that age, Harrell did not find her athletic frame to be beautiful. She became secretly anorexic and bulimic.

“As an athlete and type A student growing up, I had many reasons to see hard work taking positive effect, but unfortunately at that age and even in that era, I never often felt accomplished or powerful,” she said. “I was fit and dedicated to training as a soccer athlete in top divisions but much of what I could see of myself in the 90’s was too much difference from the models and actresses I admired.”

She overcame the body dysmorphia and included piece “Via Lactea,” a dye sublimation on aluminum, for the show “She Is.” The image is a photo of her best friend, taken a year and a half ago along in Bahai, Brazil depicting the Milky Way in the winter sky. It also serves as a self portrait for Herrell, who now only sees tremendous beauty in the athletic form.

“I staged a photo session with my long time inspiration (best friend) and revealed the incredible capabilities of her form through a cover of metallic, all over body paint,” she said. “We jumped together, spun, screamed out loud, posed hard.

“”The work from there had to embrace the lofty feeling inside the body we worked to capture.”

Harrell derived the colors by applying hue shifts algorithmically to highlights and shadows as separate values. She said that the dye sublimation on aluminum medium was necessary to further the story of this adoptive self portrait series.

“I chose a medium that offers no white point but rather a true specular and added glossy finishes to ensure that as the viewer moves toward the image, they can also see themselves in its surface,” she said. “The power of the highlights glows intensely but only at angles related to following the viewers’ position.”

Kenna Kindig

Kenna Kindig

“She Is” was Kenna Kindig’s first show after a two-year hiatus.

The artist took a break, working here and there but not really engaged, wondering if she should even be an artist.

Rejecting an idea found in conceptual art, that the concept behind the work is more important than the finished art object, Kindig returned wanting her visual art to speak for itself. She decided to show again unabashed on her stance.

Her work is mixed media of paint and collage on canvas, depicts three slender nude women in headwear.

Headdresses appear frequently in Kindig’s work, often as wearable standalone pieces.

“The crown, it’s an empirical thing. It’s a royal thing. It’s something that’s used to acknowledge status, power, placement in life, and I think especially with a queen,” she said. “The fact that it’s usually paired with a nude person is showing the weakness at the same time. Just because you’re an empowered woman or you’re an empowered person, anybody, doesn’t mean that you’re not still vulnerable.”

She said that whereas people often place items on their bodies to cover themselves or to be decorative, head coverings or hair styles can be a way to crown oneself, to hold one’s head higher.

“The head is a very regal thing,” she said. “It’s an extension of yourself, almost like, ‘hey look at me, this is me.’ ”

Before she called her work feminist, other artists called it so. She said that she had been creating from a place of having a feminine perspective but not necessarily a forwardly conscious feminist stance. The reactions to her work forced her hand on the matter.

“I think that it’s just kind of something that you can’t run away from,” she said. “It’s something just inevitable. Like, if you’re a woman and you pain women, and you care about women’s empowerment, it’s just going to happen.

“You know, I could paint pictures of flowers, but that’s not me. So, I guess I’m a feminist. I feel like its important, but I don’t feel like I have to put more emphasis on that to make myself, to put myself into a box or any other genre.”

Eleni Giagkou

Eleni Giagkou

Self-taught Greek abstract artist Eleni Giagkou spent a lifetime painting for herself.

She showed two oil paintings that had long been hanging in her house at “She Is,” emotionally watching passersby stop and discuss her work in detail at her first show. Her work depicted confidence, one painting having emerged after Giagkou left an abusive marriage.

With her 17-year-old daughter Maria Giagkou – a child from that marriage – helping to interpret by her side, the Connecticut-based artist talked about painting “My Mind” as a figure emerging from a flower as herself, and that leaving the marriage made her feel like a woman.

“Like it just came out of me. I felt like a woman,” she said. “That is my brain. (During) the time I painted it, I would go inside my brain, and I see one beautiful flower and beautiful colors and this time, and I see the canvas and take the painting and I see inside me and paint it. I love that.”

Her work emotes confidence. In an untitled oil on canvas, a bald woman standing tall with images of herself echoed behind the main figure.

In 2004, Giagkou said that she had a dream in which she saw the painted woman that watching so many people stop to note the woman was like watching the dream come alive.

A supporter of the #metoo, Giagkou said that women have always been powerful and that the movement is a step towards people recognizing this.

“Women have always been more powerful; women have been the most powerful,” she said. “Women can do anything that they can put their mind to, maybe not all are as strong physically as men, but mentally we are always stronger. And, she gives birth.”

The show runs at One Art Space, till the 20th.

Miroslava Romanova

One Art Space

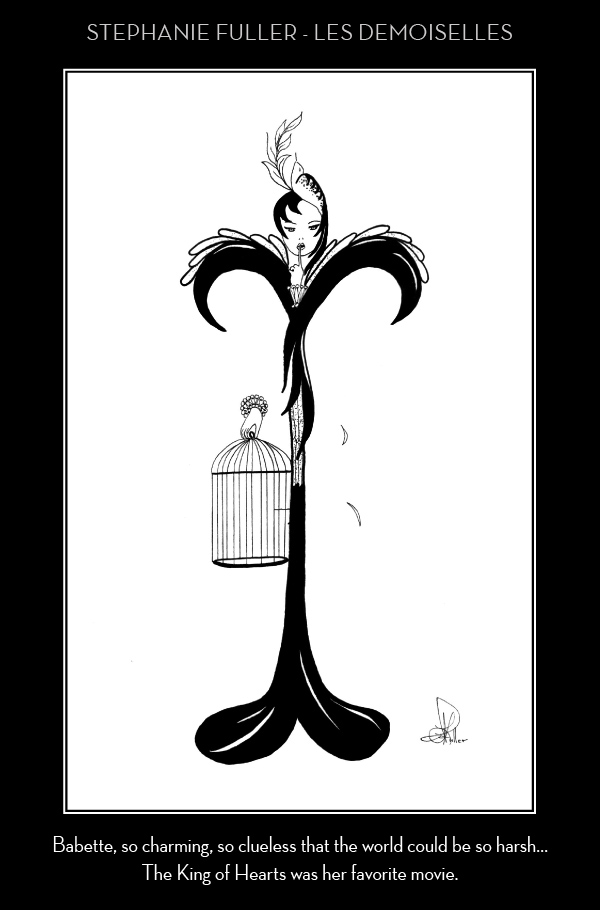

Stephanie Fuller

Adina Andrus